|

MICHAEL DOHENY Fenian Leader

(from a lecture by Michael O'Donnell (April 18, 1986)

MICHAEL DOHENY 1805-1862

Who was Michael Doheny? For most of us he was the author of the neglected work The Felon’s Track. For some he was the man who fled from the fiasco in Ballingarry in that bad summer of 1848 to walk 150 miles across Munster to little place called Dumanway, where he hoped to raise help in his efforts to escape from Ireland. Some others will know him as the writer of such hyperbolic verses as:

I’ve tracked for thee the mountain side,

And slept within the brake,

More lonely than the swan that glides,

O’er Lua’s fairy lake.

And for those with nationalist interests, he will be known as one of the prime movers in the 1840’s Confederacy in Ireland, and later one of the leading founders, in the United States, of the fenian movement.

But before there was the mature Doheny there had to be a young Doheny. One who had to be educated, to be influenced and who had to grow to maturity in some place. And Fethard was that place. More specifically, it was here in Brookhill that Doheny grew to maturity.

Michael Doheny was the third son of Michael Doheny and Ellen Kelly. He was born of 22 May 1806 in what he called Rockfield, Brookhill. It is difficult to define precisely where Doheny was born since the farm was sold before that fine reference work The Tithe Applotment Books were compiled. Local knowledge points to the spot where a flag flies today as being the site of the Doheny home. In the Doheny family there were eight children: five boys and three girls.

Fifty-three years later, writing in far away New York, Doheny had this to say of his home: "Our homestead was on the lowest part of the farm. Not far from the house were several pools of water formed by the rills that converged from the surrounding uplands. In these pools at night the geese would cluster and whisper cautiously, while nodding into rest. The neighbourhood was studded with fox coverts where foxes were kept by the gentry for their own amusement, but which were fed at the expense of the poor."

And in the same manuscript he went on to write, in that prose so beloved of so many of us when looking back from middle age to our youth: "The place of my birth was quaint, quiet and out of the way. The cricket never ceased his chirp Summer or Winter, nor was the jibbering sparrow ever idle in the thatch eaves save when he was asleep.

"In the ivy nested during the long winter nights the blackbird and the thrush; many a time as I heard them my heart leaped in anticipation of a fat prize next morning in the carefully set ‘crib’ I had arranged."

In Doheny’s young days, he writes, there were nine holdings in the Brookhill area and that rents were high; in addition the farmers had to pay a Cess, or local tax, to the Grand Jury, the body then in charge of the local administration. But the Dohenys lived comfortably according to Michael. The beggar, the piper and the scholar were always hospitably received.

But times were changing. Doheny's father became ill. And Michael tells that he was on occasion sent to guide the plough because the family could not afford a ploughman. Soon enough a greater tragedy struck: the father died. But the cup of sorrow had not passed. Following his father’s death, his mother became ill. She died after months of nursing by his eldest sister. Of this event, writing in middle age, Doheny has this to say: "Often did she, (his sister that is), spend months attending her sick mother without once undressing herself or taking a night’s natural sleep." On the personal level Michael, too, had his troubles. At the age of fourteen he got a bout of typhus; but he survived it, though it seriously set him back.

When their father died Doheny’s eldest brother, then in his teens, took over the working of the farm. As I have said Michael often helped at the ploughing by guiding the horses. This he did by sitting astride the back of one of them. The eldest boy must have also had a business-like streak in him since he employed a furze cutter to cut and bundle the furze that grew on the farm. These were sold to the local bakers for use in their ovens.

But though they had come on hard times the education of the family was not neglected. Doheny records that he received his earliest education from the wandering scholars who stayed in the farms round about. That by the age of eight he could repeat every word of Butler’s catechism by heart and knew well a number of ballads. By the age of ten a local scholar had introduced him to Dryden’s Virgil and had given him a copy of Blair’s Universal Preceptor, a grammar of the arts, sciences and general knowledge. This latter he often read while sitting astride that ploughing horse.

His sister taught him religion. And of her teaching he later wrote: "Her ethics were of the most inflexible and rigorous kind; I had to read nightly in Alban Butler’s Lives of the Saints." But out of all this he did acquire an admiration for St. Francis Xavier and greatly loved St. Augustine’s Confessions.

But his life was not all study. After all he was a normal young man with the needs of youth. He developed a passion for sports. He hurled with the local team at matches played in the local green in Fethard every Sunday. For these games, he tells us, two players would pick a team of 21; all removed their shoes and stockings, coats and hats. While playing they wore knee-breeches, flannel waistcoats and straw hats or caps. Doheny also competed in jumping and stone throwing, for which he practised at home by measuring his ground.

In 1826, when `Michael was twenty, tragedy struck again: the eldest boy died. In his autobiographical sketch Michael writes that he now inherited the farm, and of this event he says little enough beyond that as his sister proved to be "over pious and disinclined to marry" he decided to sell the farm and move into Fethard. By now the young Doheny knew a little Greek and Latin and had a working knowledge of English grammar together with book-keeping and arithmetic. Following the move to Fethard, he decided to enrol in a classical school which then existed in that place and was run by a man named Maher from Emly. After six months at this school Doheny had completely mastered both Greek and Latin.

Change came again for the young Michael. Maher decided to shift his school back to his native Emly. Doheny moved with him perhaps as a monitor in the new school, but did not stay long for whatever reason he does not tell us. From Emly Michael moved on to Thurles where he enrolled in a school run by a man named Fitzsimons. Here he began the study of logic, French and Metaphysics. While in Thurles he studied Irish, and became quite proficient in it. Alone of all the 1848 leaders he was the only one who could both read and write in the native tongue. And while on the run in 1848, down on the Cork/Kerry border, his knowledge of Irish was to be of considerable benefit to him and his travelling companion James Stephens.

After Thurles, Michael got his first teaching job in Clonmel in the Endowed School in Mary St. This school has long since disappeared having been knocked down about 30 years ago. This position he soon left, moving to become a private tutor to a wealthy family near Boherlahan whose names he does not disclose. With them he spent 2 1/2 years teaching for fifteen hours each day with three break for meals. His pupils, he tells us were two boys aged nine an twelve. From this post he moved on to become tutor to the Scully children at Kilfeacle. This family were famous as M.P’s., and notorious as landlords. The Scully family had a residence at 13 Merrion Square which was two doors from Daniel O’Connell’s home. While living here in Merrion Square he took advantage of the Scully girls to acquire a good working knowledge of Italian. To complete his time. Already he was acquiring teaching posts that were financially rewarding and bringing him to the attention of people who could better and improve his career prospects.

It was while working for the Scully family that he made his first entry into politics when he became an O’Connellite warden. A warden’s duty was to supervise the local collection for the Repeal Association of the "Tribute", the annual church-door collection on which Daniel O’Connell lived.

In August 1830, his employer Scully sent him with two of the Scully boys to Carlow College, all three of them having expressed the wish to join the priesthood. Scully gave Doheny an introduction to Bishop Doyle (the famous JKL), offering to pay his expenses in the seminary if the bishop gook him in. On their way through Kilkenny, Doheny became involved in an election celebration; but did go on to Carlow where he found that Bishop Doyle was away from home. The next day Doheny took himself back to Kilkenny as apparently thoughts of the priesthood had quickly palled. Here he joined again in what remained of the election festivities and in the course of them met a baker who told him that O’Connell would be arriving in Clonmel in a few days’ time for an election contest being held there. Doheny was then 24 years old and , though he did not then know it, was on the threshold of his career as a nationalist, an agitator and a felon.

When Doheny arrived in Clonmel, nominations were being accepted for the election. Doheny became acquainted with the election agent for the O’Connellite candidate, by what means we don’t know. Perhaps he made a point of making his nationalistic sympathies known to the O’Connell representative. Against the two Tipperary Ascendancy candidates (both sitting M.P.’s) Francis Prittie and John Hely Hutchinson, O’Connell had pitted Thomas Wyse a Waterford Catholic landowner. Wyse’s election agent was Martin Lanigan, a Templemore solicitor.

As a crude manoeuvre to prevent Wyse’s nomination, the authorities had locked the courthouse doors in Clonmel. Doheny and Lanigan got in by an adjoining house; on their arrival many of the gentry fled. When he rose to reply to the nomination speech of Nicholas Mansergh for Prittie, Lanigan collapsed; he was dead in two months. Suddenly seizing Lanigan’s notes, Michael Doheny rose and made his first public speech. His Political career had begun, a career that was to last until his death some thirty-two years later. Incidentally, Prittie, the Ascendancy candidate, came first in the election; but Wyse , the O’Connell representative, came second and got the other seat. Doheny was one of those who spoke at the celebrations that night in the Ormonde Hotel. Clonmel.

Doheny now threw himself headlong into the politics of the tithe war. He joined the Cashel Reform Club which had been founded by the new M.P., Thomas Wyse, and James Roe of Roesborough near Tipperary. I must mention that the latter in later years was to be of material help to Doheny. Throughout 1832 Doheny was in great demand at tithe meetings as well as reform and repeal meetings. He even chaired an outdoor O'Connell meeting in Cashel at which 20,000 are said to have attended. He, to round off his new political career, spent six months in gaol at the end of 1832 for his involvement in agitation. The boy from the "half-penny school" as he was once sneeringly referred to, had come a long way.

But all his work was not political. In August of 1832 an epidemic of cholera struck Cashel. Everyone who could fled the town, but not Doheny. He stayed to give what help he could. Boards of Health had been instituted to deal with this scourge, and in Cashel it consisted of six doctors and six laymen. One of those latter was Doheny. On the green outside the town two mud cabins had been turned into a hospital; so unsuitable were they that they became known as "the cabins of death". To add to the problems in Cashel the water supply failed because of the dry Summer. Day in, day out, this powerful man carried victims on his back to the makeshift hospital and buried the dead himself. Once, he tells us, he was attacked by relatives of two dead women whose bodies lay in the street because he attempted to remove them without first having a wake. By Christmas the cholera had passed, but not before there had been two hundred fresh graves in Cashel. Writing twenty years later it is only too apparent that the horror of this whole period was still as fresh in Doheny’s mind as when he lived through it.

Doheny’s friend, and one of the founders of the Cashel Reform Club, James Roe of Roesborough, now took a hand in his affairs. He financed the sending of Doheny to London to Grays Inns to study law. By Nov. 1833, Doheny had enrolled at the Inns and was lodged in 15 Francis St. now known as Torrington Place. While in London, Doheny acted as the London correspondent of the Tipperary Free Press, a biweekly paper published in Clonmel by James Hackett. And Doheny was hardly settled in London when he became involved in the agitation movement there. He attended meetings in the Bazaar, London, which was owned by the Chartist movement whose leader was Feargus O’Connor(a Cork man). And in that city he founded a branch of the Irish Repeal Association. Doheny also attended debates in the House of Commons; and he and a companion went along to a protestant and anti-Irish meetings as a heckler. So he was at more than his studies while in London.

He spent a little under two years in that city. On his return to Ireland he enrolled as a student of the King’s Inns, Dublin, having left London in the Summer of 1835. And among the barristers sworn-in at the King’s Inns by Lord Chancellor Plunkett three years later was Doheny. Through hard work and good fortune he had the foundations of an excellent career laid out for himself. He soon joined the Leinster Circuit and practised regularly in Tipperary, appearing in many criminal cases including several murder trials. And he acted as solicitor for the Cashel town Commissioners.

Among the twenty one Town commissioners elected in Cashel, under the new reform act, in Oct. 1840 were Doheny and his future brother-in-law Roger Keating O’Dwyer. In that same 1840, Doheny became a Poor Law Guardian of Cashel; in 1843 he was chairman of Cashel Board of Guardians. In 1840 also he was appointed Recorder of Clonmel by the corporation. Being a Recorder meant that he held a court some what like the present District Court, with a salary of £100 a year. In 1839 his brother James had been made District Inspector of the new national school system. The family were now moving more and more away from the poor days on the side of Brookhill.

Doheny had become a successful and prosperous figure by the 1840’s. In May 1842 he built on a plot of ground on the outskirts of Cashel a new house for himself. Some time previously he had married, Mary Jane, the daughter of the late Morgan O’Dwyer of Cashel. He, together with his new bride and her widowed mother, moved into the house which he named "Alla Aileen’. In this house four children were born: Morgan, Michael, Edmond and Jane Doheny.

The 1830’s and 1840’s were, politically, the age of O’Connell. He had the Emancipation Act successfully behind him and was now striving for Repeal of the Union. But British governments, of whatever hue, while they were prepared to negotiate on catholic questions, had no intention whatever of breaking the cords that bound Ireland and Great Britain. By the 1840’s this was apparent to both O’Connell and his young lieutenants. But the former continued to avail of constitutional means only while the latter, which included such men as Davis and Doheny at their head went even to far as to suggest that the Liberator retire and leave the field to them.

When a parliamentary seat became vacant in Tipperary in Nov. 1845 Doheny was passed over by the O’Connellite party, though he was the obvious choice. This was the beginning of the rift between O’Connell and himself. At the new Conciliation Hall in Dublin where the Repeal meetings were held, Doheny now openly differed on major policy matters with O’Connell. In Oct. 1846, Doheny terminated his membership of the repeal Association. Inevitably he was moving towards physical force as the sole means of solving Ireland’s wrongs.

Encouraged by the lesser men who surrounded him, O'Connell drove the remainder of the young Irelanders out of the Repeal Association. When in Jan. 1847, the young Irelanders formed the Irish Confederation, Doheny was present and a founder-member. So too were Smith O’Brien, Meagher, Terence Bellew McManus and Thomas Darcy McGee, the latter was later to be its secretary. Confederate clubs were formed in many parts of Ireland; many of them set about the business of procuring arms. But the threat of famine was growing daily.

Early in 1847, O’Connell’s health broke; he left for Rome, but died in Genoa on May 15. In July, a general election was held in Ireland, but Doheny was refused a hearing in Cashel. His work during the cholera plague in that town was forgotten. And the horseman of pestilence and famine were continuing to ride across Ireland. And, it has to be said, the Young Irelander’s were unfit to deal with a social and economic crisis like the famine. Young Ireland, which sought radical change only in the relations between England and Ireland, was if anything conservative on social issues.

But on land reform Doheny’s views were more extreme than most of the Young Irelanders. In Sept., he had spoken at the public meeting in Holycross at which James Fintan Lalor founded the Tipperary Tenant league. Lalor’s views on the Nation had impressed him when Doheny was working on a committee of the Confederation investigating the land question.

In a letter to Smith O’Brien on Christmas Day 1847, Doheny suggested that the Confederation proclaim itself an Irish parliament if the British parliament passed no measures to avert famine. There is, though, no hint in the letter as to what proposals Doheny had for ameliorating the catastrophe.

Early in March 1848, Dublin learned of the successful revolution in Paris and of the abdication of the French King. Riots which followed in British cities were believed to have been inspired by the Chartists, a Labour movement which Doheny supported. In the hope of getting Chartist support for the Confederation Doheny now addressed the Manchester Chartists in the Free Trade hall: and three days later, standing with Fergus O’Connor, he told a monster meeting in Oldham; "….I am an Irish Chartist….."

Following the arrest of John Mitchell in May 1848, the Confederation chose an inner council of 21; Doheny was a member of it. Two months later the government acted, against the leaders of this council. One by one they were picked up. Doheny was arrested in Cashel on 10 July, was rescued by the people, but then gave himself up and commanded the people to go to their houses and remain quiet.

A week after their arrest (they were bailed pending trial) Meagher and Doheny held a prodigious meeting of all the Confederate clubs of the South-east here on the slopes of Slievenamon on a scorchingly hot Sunday. When he came to address the meeting Doheny told the gathering; "How proud I am at meeting so many of my school-fellows who are here today to shed their last drop of blood for their country". Yet on 18 July when plans for a rising were being discussed in his house, Doheny was opposed to and armed conflict at that time. He was of the opinion that too few arms were available, that the supply of food was inadequate and that the leaders would have to rely on a famished multitude to support them. To his mind the time was wrong, and after events were to prove him right. Inside a week, following this meeting, the rising was over.

Doheny’s subsequent adventures are stirringly and vividly told in a chapter and a half of his well-known book, The Felon’s Track. For two months he led the life of a fugitive all over Munster. From Ballingarry he and O'Mahony came here to Brookhill where they were watched over by two brothers by name of Walsh while they rested. They then walked on to Carrick on Suir where they had a narrow escape from the military search parties; and where, subsequently, they were joined by Doheny’s sister who accompanied them over the Suir to Rathgormack. At Rathgormack O’Mahony left Doheny and James Stephens, who had come by a different route, joined him. Both were to be together in their walk across Munster until they left Ireland in the fall of the year. Doheny and Stephens changed their socks on their way in the church at Melleray and then went over the mountains to Dungarvan, but could not obtain a passage on a boat from here to England. After this failure both Doheny and Stephens decided to go to Kilworth and on to Dunmanway.

And here I quote from The Felons Track: "Our destination was Dunmanway, near which a friend of mine lived, in whose house I hoped we might remain concealed, while means of escape would be procured somewhere among the western headlands. A short journey brought us to this house. My friend was absent, but daughters of his, whom I had not seen since childhood, recognised and welcomed us. We had then travelled 150 miles…." And remember all this was done on foot and across country since they had to avoid public roads. Another aspect of this journey worth noting is that Doheny was then 42 years old and more attuned to a sedentary life rather than traipsing about the country.

Initially, Doheny had some misgivings about the people of Dunmanway. He had been told that they were a venal lot and would inform on him at the first opportunity. But they soon proved him wrong. He had fallen among friends. And one, a woman whose name he does not disclose, was to give him all possible help while he lay about Dunmanway; and as he wrote: "whose exertions afterwards tended mainly to secure my escape." As to whether this woman was the daughter of his friend or another we are not told. She was to be a wonderful benefactress to both Stephens and Doheny during the time they spent about Dunmanway --- taking letters and money to them, and guiding them to safe houses.

While this lady was making efforts to get the two fugitives out of the country both of them decided to visit Killarney so as to lessen the risk of detection as could well have been the case had they loitered too long about Dunmanway. Passing out of the town they followed a stream which led them into an almost inaccessible valley until they reached the south-western base of Shehigh. They crossed the summit of this mountain in their journey towards Gougane Barra and Ceimineagh; and eventually they reached Killarney.

When they had tired of looking over this beauty spot they came back once more to Dunmanway. This time they stayed at a place called Coolmountain, which may be familiar to our Cork friends, and is about six miles from Dunmanway, here Doheny revealed his identity to a local man who may have been a Protestant and no lover of those who would engage in armed insurrection. But he proved a friend indeed to the two felons. He agreed to give Doheny what help he could and , while he looked after the fugitives, he sent his wife the six miles to Dunmanway to make contact with Doheny’s lady friend in that place. This was a dangerous and compromising undertaking for this pair since both the army and police were scouting in West Cork and Kerry following reports that both Doheny and Stephens had been sighted there.

These Dunmanway friends, with the help of others in Cork, got Stephens out of the country first and on through England to Paris. Doheny had to bear with further disappointments and adventures before he too left the country. At the end of his book Doheny gives praise generously, as well he might, to his friends in and about Dunmanway who risked so much for him.

From Cork a boat took Doheny to Bristol, whence he reached Paris on 4 Oct. to join Stephens already there. Later Mrs. Doheny and the children arrived. Stephens acted as guide for the duration of their stay in that city, and no better guide could they have than this lover of French life an culture. In mid Nov. 1848 the Dohenys sailed from Le Havre; after an unusual stormy crossing, they reached New York on 23 Jan. 1849.

Though in his American diary of 1859 James Stephens was to write most bitingly and bitterly against Doheny, I do think I should quote for you what he(Stephens) wrote some twenty years after the event when he came to write on his and Doheny’s adventures together in that summer of 1848: "No man, I believe, ever made a more genial impression on me than Doheny , and the longer we remained together the deeper and more enduring that impression became. I can never resist wondering at and admiring the heroic way he bore himself in the face of his difficulties and hazardous stands we were forced to make and confront throughout that felon’s track of ours. It was nothing for a young man like me, without wife or child, to have gone on my way singing; but that he, having a woman he loved, and an interesting family he adored, to bear up as he did, as well, if not better than myself, raised him to a heroic level in my estimation. God be with him." Coming from an acerbic man like Stephens that was quite a glowing tribute, and especially when we also consider that he was not given to paying any sort of compliment to his contemporaries.

Doheny had hardly settled in New York before he plunged into Irish-American affairs. Two months after landing he had made two public appearances. He was admitted to the New York Bar and began to practice as an attorney.

Something of the fighting spirit which took Doheny from a small farm on the side of Brookhill to being an attorney in New York can be illustrated by the following two stories which occurred in Doheny’s first year in New York. Thomas Darcy McGee had earlier gone to that city before Doheny. Distrust had grown up between the two men, so one day when they met Doheny attempted to arrange a duel over some verbal disagreement they had. McGee declined and thereupon Doheny assaulted him in the street. For this Doheny was arrested but not Charged. On another occasion Doheny joined in a press controversy on the policies of O’Connell and was answered by an old O’Connellite named Patrick H. O’Conner. After a verbal exchange in the street, O’Connor struck Doheny who fought back. A duel was arranged, but on the appointed day O’Connor was found to have left for Ireland. These two events also demonstrate some of the recklessness that was a part of Doheny character. He would take up a challenge to a duel, or issue one, without any thought to the morrow or for his wife and family.

Doheny’s interest in journalism continued unabated in his new homeland. When in Aug. 1849 a new paper The Irish-American began in New York, Doheny became one of its regular writers. At this time, too, he was writing his book The Felon’s Track. Doheny‘s own ventures as an editor were unsuccessful. In May 1851 he started a monthly Republican World. It lasted ten months. Four years later he founded another, The Honest Truth, which died after six months. But throughout this period he did acquire a reputation as a lecturer and orator and was in constant demand for years afterwards.

While preparations for the 1848 revolt were being made in Ireland, a military organisation know as "The Irish Republican Union" had been set on foot in New York by a few patriots. Towards the close of 1849 the Irish Republican Union had banded into companies according to accepted military regulations and was regularly officered preparatory to its becoming incorporated into New York State Militia. Doheny, soon after this banding, was elected a captain of one of those companies: C. Company of the Irish Pike Fusiliers. In may 1850, this Irish military organisation was formally admitted into the service of the State of New York and became known as the 9th regiment New York State Militia, of Mitchell Guards. And Doheny had an interest in the famous Fighting 69th Regiment holding, by 1852, the rank of lieutenant-Colonel with a salary of £550 when on active duty. It must be noted though that such militia companies were informal bodies, and it is doubtful if the military experience gained in them amounted to much; but they had a value of another kind in keeping the fighting spirit among the Irish in America.

Another of Doheny’s interests was European socialism. This brought him into conflict with the catholic church and especially with Archbishop Hughes of New York, the idol of the poor Irish in that city, and a distinguished churchman. For Hughes, a Tyrone man, the answers to Ireland’s wrongs were not to be found in socialism however much he hated English rule in Ireland. In the 1840’s, in London, Doheny had met the exiled Italian revolutionary, Mazzini, and was impressed by his character and ideas. But Mazzini was associated with the expulsion of the pope from Rome in 1848 and Doheny’s espousal of him angered Hughes. In the early 1850’s, meetings were held in New York protesting against French support for the pope and that country’s opposition to Italian republicans,. At these meetings, time and time again, Doheny took the Italian republican side. Once more in 1852 Doheny defied Hughes by welcoming to New York the Hungarian revolutionary, Kossuth, whose religious utterances were frowned on by Catholics. Later Doheny was to publicly declare his opposition to the new French regime of Louis Napoleon, which, the church welcomed. There is evidence that Doheny knew and sympathised with the views of a French socialist theorist, Claude Pelletier, who settled in New York is 1856. Finally, in a long controversy over public schools Doheny found himself on the opposite side to the archbishop. So his relations with the leading churchman in New York could be said to have been stormy.

The fenian movement that we know so well was started, not in Ireland, but in New York in 1855. This movement grew out of the failure of a meeting that John O’Mahony and Michael Doheny held with the Russian consul in New York. The meeting took place during the Crimean War between Russia and the united armies of Britain and France. Seizing the opportunity this presented, Doheny and O’Mahony together interviewed the Russian consul. They presented him with a memorandum from the Irish military bodies asking for transport to Ireland for 2,000 men and arms for another 5,000. This request was transmitted to the Czar in Russia; but, while it was considered favourably, Russia could not afford such aid. This failure to gain Russian support was to be the reason why many of the then Irish nationalist organisations in the U.S withered and failed. But Doheny refused to be defeated. In 1855 he called together, in his law offices in Centre St., New York, those members of Irish-American groupings whose love of Ireland was still unquenched. Among those that sat down to form the Fenian Brotherhood were Doheny himself, John O’Mahony, James Roche, Thomas J. Kelly, Oliver Byrne, Patrick O’Rourke, and Captain Michael Corcoran of the 69th Regiment. Out of this meeting grew fenianism,. The title for the brotherhood came from John O’Mahony. John O’Leary considered, when he visited the U.S. in 1859, Doheny, John O’Mahony and Capt. Michael Corcoran to be the three outstanding men in the Fenian Brotherhood in the U.S.

Doheny threw himself heart and soul into the new organisation. Over the next five years he went on numerous lecture tours along the eastern coast of the U.S. and through the mid-west. These tours were used as fronts in what was an effort to organise and unite the Irish in America behind the new body and to give it the financial support so badly needed. James Stephens was contacted and given the task of organising the brotherhood in Ireland and planning for the day of rising.

An unexpected event now occurred which was to be used to whip up support for a new attempt at rebellion in Ireland and to gain recruits for the new-found Fenian Brotherhood. Terence Bellow McManus, the old Confederate leader, had died in San Francisco on 15 Jan. 1861. It was arranged that his body should be taken in state to Ireland for burial in Glasnevin cemetery, and Doheny was one of those who decided to accompany the remains on this historic journey. We are told that when Doheny saw the Irish coast for the first time in 13 years he broke down and cried bitterly. But the tumultuous welcome he received when he landed at Cork revived his spirits. At Limerick Junction the railway line was blocked by cheering crowds calling for "Colonel" Doheny. From there the cortege moved on to Dublin where Doheny had hopes of beginning a new rebellion, hopes that were quickly foiled by James Stephens who had other ideas. There followed the famous procession, on Sunday 10 Nov., through the streets of Dublin in which Doheny was one of four who formed a guard behind the hearse.

After the funeral, Doheny set out to make a return visit to his native Tipperary. The emotional welcome amazed him. At 6pm on 28 Nov. 1861, with his wife, he entered Cashel in an open carriage to be greeted by what the Clonmel Herald called the "Lower orders of the city" and the "hardly sons of toil", but it was hardly these who had covered every building with evergreens and spread banners across the rooftops inscribed "Cead mile Failte" and "Eireann go bragh".

From Cork, on 6 Dec., Doheny sailed to a United States now in the middle of a civil war. The following February he was the principal speaker at a fenian meeting in Philadelphia which considered the success of the McManus funeral demonstration. This was Doheny’s last public appearance.

Late in March he fell ill of a fever and on 1 April 1862 he died suddenly at his home in New York. A huge public funeral, led by the Irish military regiments, was held to Calvary Cemetery, New York where prayers were said by a priest representing his old sparring partner, Archbishop Hughes. Had he lived another seven weeks, Michael Doheny would have been 56 years old.

What sort of man was this Michael Doheny? Apart from some line drawings, the only description we have of him was that issued by the government publication Hue and Cry of 27 July 1848 where he is most unflatteringly described in the following terms: "Barristers; forty years of age (he was actually 42 at the time); five feet eight inches in height; fair or sandy hair; grey eyes; coarse red face like a man given to drink; high cheekbones; wants several teeth; very vulgar appearance; peculiar coarse unpleasant voice; dress respectable; small short red whiskers." Apart from that description we can only arrive at a picture of Doheny’s character from what we know of his life. He could be said to have been a reckless man. As I have told you he was not averse to indulging in the then archaic system of duelling. And when he did so he was a married man with four children. We have seen that while studying in London he became involved as a heckler at orange order meetings. A man --- a wilful man --- with the inclination of rush into things and the devil take the consequences.

And yet likeable; and a good travelling companion as James Stephens wrote. Remember that he described Doheny as a "genial companion", and that was praise indeed coming as it did from Stephens who did not too often speak well of his contemporaries and fellow revolutionaries. And we learn that in New York his son, Michael, had to protect him from the poor Irish that roamed the streets of that city. Doheny was known as a "soft touch".

He was a brave man, a man of courage. His whole live demonstrated this. His support of unpopular causes emphasised this, especially while living in New York. A fighter too, he was prepared to do battle with even Archbishop Hughes of New York, the most popular Irishman of his day.

To me he appears to have been an emotional man led at all times by the whims of his heart rather that the cold calculations of his mind. But he did not have that charisma that would have made him a leader of men. No; he was a lieutenant, an organiser, without the strengths, the single mindedness and the passion that leadership requires.

A more-or-less forgotten man. And because of that I’m delighted to see that you keep his memory, his name, alive.

Michael O’Donnell,

Owning.

18 April 1986

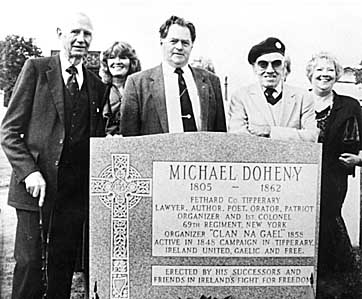

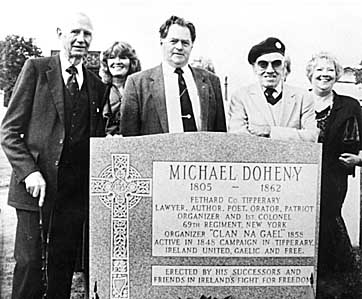

On Sunday December 4, 1988, Mrs. Mary Healy, on behalf of the Fethard Historical Society, unveiled a plaque commemorating Michael Doheny at his birthplace in Brookhill. A lecture on the “Young Ireland Rising 1848” by Dr. Willie Nolan took place afterwards in the Abymill Theatre. Ensuing coverage in the Nationalist led to an enquiry for further information on Michael Doheny from the New York Tipperary-men’s N & B Association, who erected a monument to him on 7th October 1989 at his previously unmarked burial place in First Calvary Cemetery, Section 4, Laurel Hill Boulevard, Woodside, New York. Pictured above at the unveiling are: Michael Flannery, Helen Doheny-Smith, Jim Grogan, Cashel, Paddy Doheny and Patricia Doheny.

Further information supplied to us (July 2005) by William P. Smith (husband of Helen Doheny-Smith) may be of interest to those related to, or researching information on Michael Doheny:

Mr Edmond Doheny of Fethard, residing in Cashel, passed away in the 1960's. Edmond had four children, now all believed to be deceased. Recently, a son, Edmond Doheny of Cashel passed away. He was the brother of Patrick Doheny (previously deceased). In July 2005, the Dohenys of Cashel visited America to have a family reunion. Presently living in Cashel are Edmond’s offspring, Edward Doheny, Anne Doheny-Quinn and Helen Doheny-Cullen. The late Paddy Doheny’s offspring living in America are: Michael Doheny, Kelly Doheny, Helen Doheny-Smith, Kathleen Doheny-Moltzen, Eileen Doheny-Fontaine, Maureen Doheny-Hohne and Sheila Doheny.

|